…for every time I have heard it said “Jesus spoke more about hell than anything else” (or some such variant thereof), I would have a much harder time entering the kingdom than a camel would have going through the eye of a needle. But is this beloved saying of pop-culture Christianity true? Nope. Not even close. But c’mon, we already knew this… right?

Quote

Damn, this is a juicy quote!

… a person who accepted promiscuously everything in Scripture as being the universal and absolute teaching of God, without accurately defining what was adapted to the popular intelligence, would find it impossible to escape confounding the opinions of the masses with the Divine doctrines, praising the judgments and comments of man as the teaching of God, and making a wrong use of Scriptural authority. Who, I say, does not perceive that this is the chief reason why so many sectaries teach contradictory opinions as Divine documents, and support their contentions with numerous Scriptural texts, till it has passed in Belgium into a proverb, geen ketter sonder letter — no heretic without a text?

—Benedict de Spinoza, A Theologico-Political Treatise (Dover, 1951), p. 182.

Quote

Some time ago I came across this post which relays a marvelous quote from John Wesley. I repost the quote in full:

John Wesley writing to John Trembath (August 17, 1760):

What has exceedingly hurt you in time past, nay, and I fear, to this day, is lack of reading. I scarce ever knew a preacher who read so little. And perhaps, by neglecting it, you have lost the taste for it. Hence your talent in preaching does not increase. It is just the same as it was seven years ago. It is lively, but not deep; there is little variety; there is no compass of thought. Reading only can supply this, with meditation and daily prayer. You wrong yourself greatly by omitting this. You can never be a deep preacher without it, any more than a thorough Christian. Oh begin! Fix some part of every day for private exercise. You may acquire the taste which you have not; what is tedious at first will afterward be pleasant. Whether you like it or not, read and pray daily. It is for your life; there is no other way; else you will be a trifler all your days, and a pretty, superficial preacher. Do justice to your own soul; give it time and means to grow. Do not starve yourself any longer. Take up your cross and be a Christian altogether. Then will all the children of God rejoice (not grieve) over you…

I’d love to see some stats on what and how often modern preachers read on a weekly basis, for most sermons today seem very much like ol’ Trembath’s: “lively, but not deep; there is little variety; there is no compass of thought.”

Quote

“Paul simply does not rate a prospect of future disembodied bliss anywhere on the scale of death as ‘salvation’, presumably since it would mean that one was not rescued, ‘saved’, from death itself, the irreversible corruption and destruction of the good, god-given human body. To remain dead, even ‘asleep in the Messiah’, without the prospect of resurrection, would therefore mean that one had ‘perished’.”

—N. T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God (Fortress Press, 2003), pp. 332-333.

No Marriage in Heaven?

I had the common “’till death do us part” phrase taken out of my wedding vows, replacing it with “’till God do us part.” The reason was partly because the phrase is odd in itself. Why would anyone, much less a Christian, give death power over one’s marriage? Death does not by itself dissolve a marriage, even if it makes a marriage soluble. But the other, more significant reason is that I am utterly unconvinced by the fundamental axiom of status quo Christianity that “there is no marriage in heaven.” This line is mindlessly parroted as if it were as obvious as the existence of the external world. The overbearing confidence derives from a naïve reading of the following passage:

That same day the Sadducees, who say there is no resurrection, came to him with a question. “Teacher,” they said, “Moses told us that if a man dies without having children, his brother must marry the widow and raise up offspring for him. Now there were seven brothers among us. The first one married and died, and since he had no children, he left his wife to his brother. The same thing happened to the second and third brother, right on down to the seventh. Finally, the woman died. Now then, at the resurrection, whose wife will she be of the seven, since all of them were married to her?”

Jesus replied, “You are in error because you do not know the Scriptures or the power of God. At the resurrection people will neither marry nor be given in marriage; they will be like the angels in heaven. But about the resurrection of the dead—have you not read what God said to you, ‘I am the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob’? He is not the God of the dead but of the living.” (Matt 22:23-32)

The encounter is recorded in the other synoptics as well (Mark 12:18-27; Luke 20:27-38). I want to ask two questions: Does this passage give us good reason to think that there will be no marriage in heaven? and Are there any reasons to think there will be marriage in heaven? Taking them in order, then:

I. Does this passage give us good reason to think that there will be no marriage in heaven?

The answer is no. The following points have been made before, but apparently they cannot be made enough.

1. The passage is not about angels or heaven. This is the first thing that needs to be said. I can’t say how many times I’ve heard it said that there is no marriage in heaven because we will be like the angels in that either (a) the angels are genderless (whereas marriage is between a man and a woman), or (b) the angels are immaterial, bodiless beings (whereas marriage, founded on the command to procreate, is rendered obsolete sans the possibility of physical intercourse).

This is a ridiculous interpretation, not least because it misses precisely what the passage is about; namely the status of the resurrected. The resurrected will have physical bodies. That’s what it means to be resurrected. Because it forgets this, it misidentifies the relevant respect in which the resurrected are like angels; i.e., being immortal (more on this below). The fact that the question on the minds of status quo Christians is always framed in terms of whether there will be marriage in heaven, as opposed to in the resurrection, is telling: the status quo interpretation is unduly influenced by a non-Christian, Platonic pie in the sky bye and bye idea of heaven. As such, the interpretation is also absurd because it makes grand, unwarranted assumptions about the nature of angels and “heaven.”

1.1. Nothing in the Bible compels us to think of angels as genderless or bodiless. If anything, angels always appear to be male. But more interestingly, the characteristics ascribed to angels in the Bible bear an uncanny resemblance to the characteristics of the resurrected body: (i) angels can appear and disappear similar to how the resurrected Christ is said to; (ii) on at least one occasion, Jesus’ post-resurrection appearance inspired fear and terror in the minds of the disciples, just as an angelophany might (Cf. Luke 24:1-5); (iii) angles, like Paul’s description of the resurrected body, are radiant with glory, powerful, and immortal; (iv) Jesus, when he ascended to heaven, didn’t slough off his acquired human nature. This means that heaven, even now, must be compatible with having a physical body, at least a supernatural one like Christ’s resurrected body (taking Christ’s resurrected body as paradigmatic, it might also suggest gender is retained). So, the fact that Jesus says the angels are in heaven does not mean the angels are in an immaterial, bodiless state. (It hardly needs to be added that this is not to say one becomes an angel upon being resurrected; no, just that but how the resurrected are said to be like angels may well include having a supernatural body.)

1.2. “Heaven,” in fact, is mentioned merely en passant and bears no rhetorical weight for the point Jesus is making. N. T. Wright comments on the passage:

This last phrase does not mean ‘they, like angels, are in heaven’. It does not refer, that is, to the location of the resurrected ones, however easy it is for late western minds to assume that it should. After all, had first-century Jews believed that people ‘went to heaven when they died’, they might well have supposed that marriage continued in that sphere; mentioning the location of the departed would not have made Jesus’ point. Rather, as some later scribes tried to make clear, it means ‘they are like the angels who are in heaven’, or, if you prefer, ‘they are like the angels (who happen to be in heaven)’, as I might say to my nephew in London, ‘You are just like your cousin (who happens to be in Vancouver).’ (Resurrection of the Son of God, pp. 421-422)

It could be that the only reason Jesus mentioned angles and heaven at all was to take an additional swipe at the Sadducees, as it is thought that they also denied the existence of angels and any notion of a lively afterlife. You could delete the entire “like the angels in heaven” clause from all three accounts and no part of Jesus’ point would be lost. Pointing out that the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob is the God of the living is sufficient for making the point about immortality. This consideration alone exposes just how flaccid this status quo Christian axiom is, based solely as it is on an afterthought clause of eight words.

2. The passage is about Levirate marriage, not necessarily marriage generally. The problem the Sadducees present is premised on the Levirate practice where a man takes his childless widowed sister-in-law as his wife to ensure that his deceased brother’s bloodline will not die with him. Once this is understood, the relevant sense in which the resurrected will be like angels, as Luke’s account makes clear, is clear: they will be immortal (Luke 20:36). What could be more obvious: if you are immortal, there is no need to beget children to carry on your lineage. Wright explains:

The Levirate law, quite explicitly, had to do with continuing the family line when faced with death … A key point, often unnoticed, is that the Sadducees’ question is not about the mutual affection and companionship of husband and wife, but about how to fulfill the command to have a child, that is, how in the future life the family line will be kept going. This is presumably based on the belief, going back to Genesis 1.28, that the main purpose of marriage was to be fruitful and multiply. …[T]he question about the Levirate law is irrelevant to the question of the resurrection, because in the new world that the creator god will make there will be no death, and hence no need for procreation. Jesus has addressed the question’s presupposition, undermining the need to ask it in the first place. (Ibid., p. 423)

Similarly, Ben Witherington:

Where there is no death, there is no need or purpose either to begin or to continue a Levirate marriage. The question the Sadducees raise is inapplicable to the conditions in the new age. On this interpretation Jesus is answering specifically the case in point without necessarily saying anything about marriage apart from Levarite marriage. (Women in the Teaching of Jesus, p. 34)

So, Jesus is at least saying that the resurrected will not participate in Levirate marriage. Witherington further suggests two reasons to think Jesus’ response did in fact concern only Levirate marriage. “Perhaps, like many of the rabbis,” Witherington muses, “Jesus distinguished between marriage contracted purely for propagation and name preservation, and the normal form of marriage” (p. 34). This is more likely than not given that “Jesus recognized that non-Levarite marriage had a more substantial origin, purpose and nature than merely the desire to propagate and maintain a family name” (ibid.). Second, Witherington senses “a negative evaluation of Levirate marriage” in Jesus’ response to the Sadducees’ question, which “would further support His attempts to give a woman greater security and dignity in a normal marriage, and give her the freedom to feel that raising up a seed through Levirate marriage was not a necessity” (p. 35). Levirate marriage, like other Deuteronomic laws, fell out of use once the conditions for its institution became less common. By Jesus’ day, life expectancy was higher and clan identity was less palpable.

3. But even supposing Jesus is making a point about marriage generally, it is a point of limited scope. If marriage in general is in view, we can at most infer that the act of getting married will not occur in the resurrection. Witherington points out that the terms for “marry” (γαμοῦσιν) and “be given in marriage” (γαμίζονται) “reveal that the act of marrying, not necessarily the state of marriage, is under discussion. Thus, the text is saying, no more marriages will be made, but this is not the same as saying that all existing marriages will disappear in the eschatological state” (p. 34).

To summarize our answer to the first question: It’s not clear from this passage that Jesus had marriage in general in mind, as opposed to just Levirate marriage, and even if he did, it does not amount to unrestricted abolition of marriage in the resurrection.

II. Are there any reasons to think there will be marriage in heaven the Resurrection?

We should agree that there is no marriage in the resurrection insofar as its purpose is to procreate in the face of death. But it is hardly insignificant that marriage was instituted prior to the fall; i.e., before death had entered the world. The institution of marriage forms a union grounded in God and the created order He calls good. We cannot equate, then, a deathless world with either a marriageless world or a world without procreation. If God is about re-storation and re-creation, undoing what sin and death has done, there may well be other purposes for marriage and/or procreation in heaven, such as a sui generis form of companionship. If you’re tempted to rejoin, “but the resurrected will have no need for companionship other than God!” I will agree, but note that God saw that it was good to give Adam a companion despite the fact that He was already with Adam in the garden. And it’s not that Adam needs a companion; it’s rather that God showers upon Adam blessings well beyond necessity. Indeed, God didn’t need to create. But he did. God’s act of creation, and His command for us to be fruitful and multiply, illustrates well the Medieval dictum that bonum est diffusivum sui: it is the nature of goodness to spread itself out. The unity of marriage is not only good, but very good. And if the Genesis narrative tells us anything, it’s that disrupting unity is not good.

I’m not saying this is a decisive reason to think there will be marriage in the resurrection. But the possibility is worth taking seriously. At any rate, we can safely conclude with Witherington that

Nowhere in the Synoptic accounts of this debate are we told that we become sexless, without gender distinctions like the angels, or that all marital bonds created in this age are dissolved in the next. The concept of bodily resurrection indicates that there is some continuity between this age and the next which leaves the door open for continuity in the existence of marriage (p. 35).

More can and has been said. See excellent discussions here and here and here and here.

14 Favorite Ways to Twist the Gospel

Don’t miss Howard Snyder’s 14 Favorite Ways to Twist the Gospel. They are among my favorites as well.

Blogospheric Pollution

The blogosphere is at least as polluted as the atmosphere. But then again, the blogosphere was never really known for having clear waters of crisp distinctions or the fresh air of well-defined terms. Witness exhibit A by a well-meaning but confused Christian who should know better:

And all that leads me to ask this question w/o much emotional attachment: Would you consider me a blasphemer for thinking that Muslims and Christians worship the same God? Cuz … I do. And I know – that could get me slapped in some circles.

The “all that” refers to the recent controversy over whether Malaysian Christians can refer to the Christian God using the name “Allah.” And to this my enlightened friend courageously stands for—though “w/o much emotional attachment”—his belief that “Muslims and Christians worship the same God” against the threat of heresy. Yes, you have heard it said, “Muslims and Christians worship the same God.” But I wonder from whom. From some equally enlightened, profoundly original Western news journalist whose infatuation with Islam is matched only by his contempt for conservative Christianity, no doubt.

It is true that “Allah” is the Arabic word “God,” and is historically referentially indiscriminate with respect to which God. “God,” like “Allah” is a generic term that can be used to refer to different things, in the same way that “truck” can be used to refer to a Ford F-150 or an 18-Wheeler. Of course, the referents may have certain properties in common. Both trucks have wheels and an engine. Both the Christian and Muslim God are omnipotent and omniscient. But two things having something in common doesn’t mean they’re the same thing. I have ears. Elephants have ears…you see where I’m going. So, same word, different referent. More precisely: words refer to concepts and concepts denote things. So: same word, different concepts, different things. This is not hard, people.

In what ways, then, do the Christian and Muslim concepts of God differ? They are probably more dissimilar than they are similar, but the essential difference is this: the Christian concept of God is trinitarian. God is three persons. The Muslim concept of God is unitarian. God is one person, not three. But if the concept of A differs essentially form the concept of B, then A and B cannot possibly denote the same thing. So if either a Christian or a Muslim thinks they’re worshiping the same God, they have simply failed to understand the concept of the God in whom they claim to believe. If a Christian is worshiping the same God as a Muslim, one or the other is worshiping the wrong God. In fact, one doesn’t exist.

Again: the same word can refer to different concepts which denote different things. “God,” then, cannot be assumed to refer to the same concept when used by Muslims and Christians. It bears repeating because this is apparently difficult stuff for some. So in situations like this, one can adopt one of two solutions: either specify what one means by the word or use different words. For Arabic-speaking Christians and Muslims, the former route seems most reasonable. For Westerners who already have two words handy (i.e., “God” and “Allah”), each one having very different connotations, the latter route seems most reasonable. As Muslim Badru Kateregga says (Kateregga and David Shenk, A Muslim and Christian in Dialogue [Herald, 1997], p. 23):

Muslims feel strongly that the English word God does not convey the real meaning of the word Allah.

And Christians should agree. Let us therefore adopt the second solution. Different words (nearly always) flag different concepts, helping to preventing confusion. This problem highlights the importance of words. Words are the vehicles of meaning that serve to make oneself understood and to understand others. As Jonathan Edwards puts it, “it is much the more hard to think right when speaking so wrong.” Saying “Muslims and Christians worship the same God” should be just as offensive to Christians as it is to Muslims, and so should be found on the lips of neither. Why? Because it suggests that one of them is an idolater. If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the pollution.

Of Mystics and Men

I was recently reminded of the following oft-misquoted passage from Jonathan Edwards’ book, Religious Affections:

As the first comfort of many persons, and their affections at the time of their supposed conversion, are built on such grounds as these which have been mentioned; so are their joys and hopes and other affections, from time to time afterwards. They have often particular words of Scripture, sweet declarations and promises suggested to them, which by reason of the manner of their coming, they think are immediately sent from God to them, at that time, which they look upon as their warrant to take them, and which they actually make the main ground of their appropriating them to themselves, and of the comfort they take in them, and the confidence they receive from them. Thus they imagine a kind of conversation is carried on between God and them; and that God, from time to time, does, as it were, immediately speak to them, and satisfy their doubts, and testifies his love to them, and promises them supports and supplies, and his blessing in such and such cases, and reveals to them clearly their interest in eternal blessings. And thus they are often elevated, and have a course of a sudden and tumultuous kind of joys, mingled with a strong confidence, and high opinion of themselves; when indeed the main ground of these joys, and this confidence, is not anything contained in, or taught by these Scriptures, as they lie in the Bible, but the manner of their coming to them; which is a certain evidence of their delusion. There is no particular promise in the word of God that is the saint’s, or is any otherwise made to him, or spoken to him, than all the promises of the covenant of grace are his, and are made to him and spoken to him; though it be true that some of these promises may be more peculiarly adapted to his case than others, and God by his Spirit may enable him better to understand some than others, and to have a greater sense of the preciousness, and glory, and suitableness of the blessings contained in them. [(Dover, ed. 2013) pp. 151-152]

This is one of those juicy quotes that in embellished form floats around the internet without bibliographic citation. At the time of Edwards’ writing, the “inward” trend of emphasizing an intensely subjective, mystical “personal relationship” with God was gaining momentum, which found full expression in the American revivalist preaching of the 1800s. Tellingly (as J. P. Moreland has pointed out in Love Your God with All Your Mind, p. 23), three of the major American cults emerged at that time: Mormonism, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Christian Science.

I once found a Christian tract in an airport “religious observance” room that had the phrases “personal relationship” and “know Jesus as your own personal Savior” almost every other sentence. The tract was so chalk full of these phrases that had I tried to write a tract satirizing this trend, I might have reproduced the same tract. I wish I still had it.

What do these phrases even mean? The idea that having a “personal relationship” with God means that God guides by whispering in your ear or “puts something on your heart” is unbiblical, lazy, self-centered, and immature. The modern notion of “listening to the voice of God in your heart” or “being spoken to by God” in some personal, subjective way as part of a normal and mature relationship with God is indelibly vague, confusing, and, I suspect–along with Edwards–delusional. The false expectations created by the inward trend has adversely affected the way we communicate to God and even the primary way He communicates to us; i.e., through his Word. The Bible is no longer a sober book of divine wisdom that means what it says. The Bible is latent with magical powers and Bible studies are séances.

Does this mean there’s nothing meaningful or true in the phrases? No. Does this mean God doesn’t communicate personally to individuals? No. But those are topics for another post.

How to be a Super-Duper Christian

This is an amusing video that pokes fun at the absurdity of short-term mission trips. He hits many of the same points I have before.

Not Dying is Not Sufficient

Christianity is all about resurrection. It is crucial, therefore, to recognize and try to understand the importance of resurrection. One way to not do that is by playing fast and loose with the term “resurrection”. This is easily and often done, for example, by identifying Jesus’ raising Lazarus or Jairus’ daughterfrom the dead as Jesus’ resurrecting Lazarus or Jairus’ daughter.

Jesus raising Lazarus, et al. from the dead may have been a sign of what was to come (resurrection), but it was not the thing itself. It would be more accurate to speak of the revivification of Lazarus, or simply Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead (although even “raised” in most contexts refers to resurrection proper). What, then, is the key difference between resurrection and these other cases of rising from the dead?

Some, who although are careful to distinguish resurrection from these other cases, nonetheless miss the key difference. The difference is not, as is commonly thought, that those who are resurrected will not taste death again, whereas those who are merely raised from the dead will. It is true that the resurrected will not die again. That, however, is a necessary but not sufficient condition for resurrection. Consider: suppose after Jesus raised him from the dead, God assumed Lazarus into heaven like He did Enoch and Elijah. We’d have a case of rising from the dead without a “second death,” but still not resurrection.

Some, who although are careful to distinguish resurrection from these other cases, nonetheless miss the key difference. The difference is not, as is commonly thought, that those who are resurrected will not taste death again, whereas those who are merely raised from the dead will. It is true that the resurrected will not die again. That, however, is a necessary but not sufficient condition for resurrection. Consider: suppose after Jesus raised him from the dead, God assumed Lazarus into heaven like He did Enoch and Elijah. We’d have a case of rising from the dead without a “second death,” but still not resurrection.

The key difference is that the resurrected have the transformed, glorified body; the kind that allowed Jesus to (apparently) walk through walls and the kind Paul describes in 1 Cor 15. The resurrected won’t die again precisely because death can’t touch the transformed body. To repeat, it is not because Lazarus died again that his rising wasn’t a resurrection; it it because he wasn’t raised with a transformed body. CARM rightly sees the glorified body as salient, but confusedly distinguishes two kinds of resurrection rather than distinguishing resurrection from revivification or raisings from the dead. This, again, plays fast and loose. There is no resurrection without a glorified body.

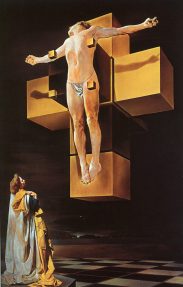

This is one reason I love Dali’s Corpus Hypercubus, where Christ is hanging on an unfolded hypercube, which happens to take the shape of a cross. More popularly interpreted to mean Christ’s divine nature can’t be fully grasped by us, the wound-less body on the rising cross calls to my mind resurrection–there’s something ‘extra-dimensional’ about that restored, radiant body, the hypercube representing both that extra-dimensional reality as well as the gateway to it.